NARRATIVE FRAGMENTS - ONE WEEK REMAINING

Yesterday's Art walk was a great success! Thanks to the hundreds of people who came out to visit all of the galleries on Gallery Row, we had a wonderful time discussing Ricahrd's work with everyone. With only one week remaining in the show, make sure to head down before it closes on the 30th of June. To further entice you in, some reading material on the work....

In the modern era the tripod typically

functions as a mute, level support for a camera, telescope, surveying apparatus

or compass. Cameras and telescopes allow individuals privileged and delimited

views of the world and of the universe. The surveyor's instrument and the

compass are locational devices; the first offers a view of the world for the

purposes of measuring, delimiting and establishing relative dimensions while

the second helps establish relative location and direction. Altogether these

instruments help situate and define one's relative place in a measurable world.

Tripods have a long association with surveyors, at the origins of architecture.

Yet equally ancient is the tripod’s function in relation to the Greek oracle.

The tripod supported both the vessel commonly found at the sacred shrine at

Delphi and the seat on which the Pythian priestess sat in delivering the

imprecise and oft-misunderstood oracles of the god Apollo.

With his tripod sculptures Henriquez

refers to all these meanings of the tripod, to vision and the visionary, even

as he alters the tripod’s function and meaning, from a support for a scientific

or religious ‘view-finder’ to an ‘object to be viewed.’ Instead of supporting

equipment for measuring space or seeing into the future, Henriquez’s tripods

hold poetic assemblages that require viewers to look inward in order to

untangle their open-ended meanings.

|

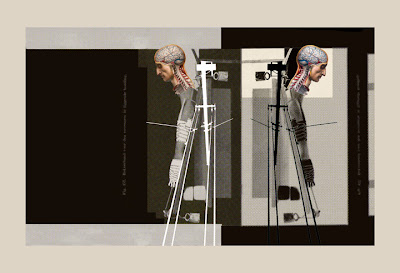

Bandages I, 2012

Archival Ink-Jet Print with wood & canvas,

25.375 x 39.75”,

|

The tripod is a model of efficiency. It

provides stable support with the minimum of legs while its adjustable

extensions enable it to adapt to the height of any user and to deliver a level

support that can be deployed in any direction no matter how irregular the

topography. When not in use its legs can be collapsed for easy portability or

storage. For the exhibition Richard Henriquez: Narrative Fragments

at the Winsor Gallery Henriquez contradicts the mobility, adaptability and

function of the tripod by attaching prosthetic shadows onto each of his

tripod’s legs. These prescribed shadows suggest a fixed source of light for a

static object, like those cast by a sculpture in a gallery, instead of the

unpredictable and changing shadows that would apply to a working tool.

A source of inspiration for Henriquez’s

prosthetic shadows comes from Marcel Duchamp’s 1913-14 work 3 Standard Stoppages, an anti-instrument

with which the artist playfully commented upon Albert Einstein’s 1905 Theory of Special Relativity. Duchamp

was specifically interested in Einstein’s notion that movement through time and

space could modify the standard metre measure. Whereas Duchamp used the random

results from rigidly applied procedures to create a set of quasi-scientific

devices that measure the relativity of distance (each stoppage is a different

length), Henriquez follows an equally rigorous method in producing the opposite

result, an artwork with the built-in certainty of a fixed light source.

Marcel Duchamp casts another shadow

over other works presented in the Winsor Gallery exhibition. Henriquez has long

been a bemused opponent of Vancouver’s zoning laws, particularly the imposition

of view cones aimed at preserving pre-ordained views from the city centre to

the surrounding landscape. Henriquez’s ironic response is a massive new

skyscraper, one that obviates the need for view cones by housing the city’s

entire population in a single tower. Now everyone can see the mountains! As if

in answer to the question, what would Duchamp think? Henriquez has deployed the

Surrealist artist’s most famous work, The

Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-23), also known as the Large Glass, as part of a theoretical

skyscraper project, presented in the form of a physical and digital model.

Henriquez virtually transports this large and extremely fragile artwork to

Vancouver (on the back of a massive paper airplane), from its home at the

Philadelphia Museum of Art, to form part of this 2,500-foot tall skyscraper,

formed by the seismic shifting and 90 degree rotation of five city blocks.

|

Honeymoon Suite #3, Arriving in Vancouver,

2012, archival ink-jet on canvas, 48 x 72”

|

The project builds upon Henriquez’s

1985 drawing Vertical City for a

skyscraper at the foot of Burrard Street, the façade of which was generated

from the surface pattern of the facing street grid (floors corresponded to

horizontal cross streets, elevator lines to principal vertical boulevards). And

there is also a correspondence with his 1989 Presidio condominium, whose design

was generated from an invented narrative involving the transposition of Adolf

Loos’s 1906 Villa Karma from Switzerland to Vancouver’s West End. There may

also be a distant nod to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mile-High skyscraper project of

1956, The Illinois, that was meant to

house 100,000 and to “mop

up what now remains of urbanism,” according to Wright.

The

series of digitally produced collages that

complete the works in this exhibition continue Henriquez’s preoccupation with

Marcel Duchamp, for instance the Surrealist artist’s intention that his Large Glass be neither a painting nor a

sculpture, but rather a work of art “to be looked through and at.” The collages

are layered yet transparent and are composed of fragments that are often

disposed in mirror-image relationships. Henriquez’s collages share with

Duchamp’s work a seemingly contradictory working method that combines the

randomness of chance procedures, the rigor of scientific or technological

processes and the laborious hand-made practices of craftsmanship. The collages

typically comprise three layers of overlaid Plexiglas, each sheet carrying a

separate imprinted image and with some of the layers backlit by LED light

panels. This of course is perverse because the overlaid layers existed as a

single image on his computer and could more easily have been printed on one

surface. But Henriquez wants you also to be aware of the means by which the

work was created just as he wants to deny the computer’s facility in producing

perfectly reproducible pictures. He transforms digitally produced images into

handcrafted objects that become works of art “to be looked through and at.”

- Excerpt from Howard Shubert's Mechanamorphic Dreams Essay for the Narrative Fragments Exhibition at Winsor Gallery, 2012.

Comments

Post a Comment